Donation after circulatory death program in Italy

Lung transplantation is a consolidated clinical reality and has become a worldwide established procedure for selected patients suffering from end stage pulmonary failure. In time, the number of such procedures has been increasing, showing substantial improvement in both patients’ survival and quality of life. However, these outcomes are still affected by both early and late complications (1). Nevertheless, significant differences among countries exist, mostly with regard to organ donation and donor management. Culture, ethics, and law seriously affect these aspects; surgical techniques and recipient postoperative care, instead, appear more homogeneous.

The Italian donation system

Consent to donation and death declaration

In Italy, a presumed consent law for organ donation was approved in 1999, stating that citizens were to express their willingness or refusal to donate organs after death. Their choice is then recorded in the national organ donor registry. By law, the absence of such declaration is considered consent (2). However, this law has never been enforced, and a mixed “opting-in” and “opting-out” system has been applied to date. Organ and tissue recovery are only possible after death declaration and after confirming the willingness to donate in the national registry, or, in absence of an expressed preference, after obtaining the non-opposition by the donor’s next of kin. According to Italian law, death is defined as the irreversible loss of brain function (3); the determination criteria, both neurological and cardio-circulatory, were established by a decree (4) in order to guarantee the observance of the dead donor rule: organ recovery must not cause the death of the donors, who must be dead before the beginning of organs procurement. For adult patients showing encephalic lesions who are in a state of unconsciousness, have neither brainstem nor respiratory reflexes, and whose electroencephalogram (EEG) shows electro-cerebral silence, brain death is confirmed after 6 hours. During this observation period, the patient is tested at least twice to confirm the loss of brain and brain-stem functions (i.e., absence of reflexes, hypercapnia and acidosis, flatline EEG). Cardiac death ascertainment is based on the cessation of cardio-circulatory functions: according to Italian law, 20 minutes of flat electrocardiogram (ECG) must be recorded in order to declare the patient’s death, as it testifies to the total loss of cerebral functions. In both cases, death is ultimately defined by the cessation of brain activity: with neurological criteria the loss of brain function is directly demonstrated, while in case of cardiac death it is guaranteed by the prolonged lack of cerebral blood flow.

Lung allocation system

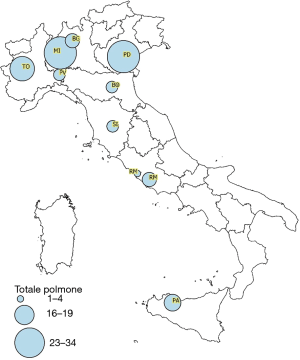

In Italy, there are ten lung transplant centres, including one managing paediatrics only, coordinated by a well-established national and regional transplantation network (Figure 1). When a potential donor is referred by the intensive care unit (ICU) staff to the regional coordinating centre [Centro Regionale Trapianti (CRT)], lungs are primarily allocated to urgent patients included in the Italian Urgent Lung Transplant (IULT) program by the National Transplantation Centre [Centro Nazionale Trapianti (CNT)], the national coordinating centre. The IULT program was instituted in 2010: urgent patients are put on a single national waiting list. The priority of each patient lasts 1 week and can be renewed twice. The IULT program inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1 (6). If there are no urgent recipients, organs are allocated within the region. As opposed to the other Italian regions, where there is only one lung transplant centre, in Lombardy, the most densely populated in northern Italy (422,76 inhabitants per square kilometres), there are three lung transplantation centres, including our own. In our region, since March 15th, 2016, lung allocation is no longer “centre oriented” but “patient oriented”, as Lung Allocation Score (LAS) has been applied. The positive experiences in the United States first and then in Germany led the Lombardy Regional Reference Centre to merge the three centres waiting lists and implement LAS for the allocation of lungs within the region (7). Finally, it should be pointed out that Italy’s elongated and narrow morphology (Figure 1), its great number of mountains, covering 40% of the country’s territory, and the presence of two large islands (Sicily and Sardinia) make rapid and timely transportation of the retrieval team and the grafts quite complicated. These peculiar geographical features might be the cause of very long transfer times for relatively short distances.

Table 1

| IULT program inclusion criteria |

| Patients on the waiting list dependent on mechanical ventilation and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenator (except for Extracorporeal Carbon Dioxide Removal device) |

| Patients hospitalized at the transplant centre |

| Age ≤50 years old |

| Absence of sepsis, multi-organ failure, haemorrhagic shock, neurologic impairment |

Italian transplantation experience

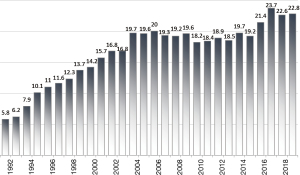

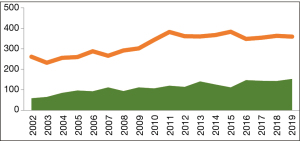

During the last 20 years, the number of potential donors referred by ICUs and consequently the organ donation activity in general, has been progressively growing (Figure 2). However, as the amount of lung transplantation procedures performed in Italy every year has almost tripled, increasing from 60 lung transplantation in 2000 to 153 in 2019, the number of patients on the waiting list has also slowly yet significantly been rising. The average time period spent on the waiting list for lung transplantation, according to the 2019 CNT report, was 2.5 years (5). At the time, the most severe limitation was, and still is, the shortage of suitable donors. The dramatic consequence of the gap between supply and demand of donor graft was high mortality for patients on the waiting list. The graph shows the gap between the patients on the waiting list and the number of transplants per year in the last 5 years (Figure 3). Several strategies have been implemented to overcome this shortage, such as the use of extended criteria donors (ECDs) and the donation after circulatory determination of death (DCD). Over the years, particularly at the beginning of the lung transplantation era, only “ideal” lung donor grafts were considered for transplantation. However, most of the potential donors in ICUs do not even meet the criteria defining a “standard” lung donor (Table 2). In fact, despite careful management, the prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU damages the lungs and the other organs. In Italy, only 40% of referred donors are suitable for multiorgan procurement, and, barely 15–20% of them are considered for lung transplantation, also due to their advanced age. Protocols regarding potential donors’ management have been applied in Italian ICUs in order to maintain the donor stability and optimize the organs’ condition. At the same time, transplantation centres started pushing the limits by accepting organs from donors with increasingly extended criteria. For this reason, research started focusing on finding a way to thoroughly and safely evaluate these “extended criteria” grafts.

Table 2

| ABO compatibility |

| PaO2 >300 (FiO2 =1.0; PEEP =5 cmH2O) |

| Age <55 years old |

| Absence of infiltrates at chest X-ray |

| Absence of secretions/aspiration signs at bronchoscopy |

| No history of cardiothoracic surgery |

| Adequate size match |

| Smoking history <20 pack/years |

| No trauma of the chest |

PaO2, arterial oxygen pressure; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

Ex-vivo lung perfusion (EVLP)

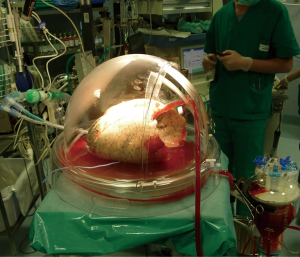

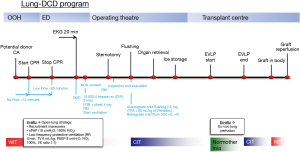

The advent of EVLP provided a fundamental tool for lung transplantation centres, allowing for detailed assessment and reconditioning of lungs. In Italy, machine perfusion protocols vary among centres (8,9). In our centre in Milan, we perform a 4-hour-long normothermic EVLP with an open atrium technique, using a perfusion solution made of both Steen solution and red blood cells (reaching a 5–10% haematocrit) and maintaining the target flow at 40% of the estimated donor’s cardiac output, as previously described (Figure 4) (10). Our clinical experience with machine perfusion began in 2011, when our team performed the first lung transplantation after EVLP in Italy, and we have been using it ever since, with good results (11). In 2016, we started using portable organ care system (OCS) for selected cases as well. EVLP proved a valuable resource, as it helped increase the number of lung transplantations performed in our centre, it allowed us to assess and transplant lungs from donors on extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support and to act as a “lung repair centre” (12). Furthermore, EVLP opened up the possibility for our centre to implement a DCD lung transplantation program.

DCD donors

DCD describes the retrieval of organs following death, according to circulatory instead of neurological criteria. The definition of death and the dead donor rule remain the same and must be respected. The first lung transplantations were performed from DCD donors; conversely, following the publication of the Harvard criteria, donations from brain death donors (DBD) gained consensus. In 1995, a renewed interest in DCD sparked; the procedure has later become widespread with the experience of Steen in 2001 (13,14). At present time, the DBD setting still remains the most common. The determination of death following neurological criteria allows keeping the organs viable inside the donor but, at the same time, represents a potential source of damage to the lungs. Potential noxae are the resuscitation manoeuvres themselves, and the effects of two so-called “storms”, which usually occur during brain death: the pro-inflammatory cytokines storm and the catecholamines storm. In this scenario, donors from DCD overcome these obstacles; moreover, the resistance of pulmonary cells to ischemia due to the absence of circulation and the possibility of dissociating ischemia from hypoxia by means of ventilation are both well known (15).

Classification

In 1995 in Maastricht, the First International Workshop on DCD drafted four categories of patients in order to outline the approach to this type of donors (16); the classification has undergone some changes since its original inception, but the fundamental concepts have remained the same. Specifically, it is possible to identify two settings, uncontrolled and controlled: the first two categories include donors qualified as uncontrolled DCD (uDCD), because cardiac arrest occurs unexpectedly. Additionally, the clinical history of the donor is unknown. In this setting, the greatest difficulties concern the logistical and organisational aspects, as well as the need to thoroughly evaluate the organs. Conversely, we refer to those in the third category as controlled DCD (cDCD) donors, since the procurement is substantially planned after an anticipated cardiac arrest, and donors are largely evaluated in time. For category III donors, the most relevant problem is of ethical nature, and it is related to the suspensions of treatment. Category IV includes brain-dead donors who suffer an unexpected cardiac arrest after death declaration and before organ retrieval has been planned. The modified Maastricht classification of DCD also includes a fifth category, comprising organ donation after euthanasia, which is illegal in Italy.

Differences around the world

Around the world, experiences with DCD are extremely diversified. Notably, some countries do not allow organ DCD (i.e., Germany). The differences among countries mainly depend on local factors regarding culture, logistics, law, ethics and religion. To this, we must add the graft factors, as each organ has its peculiar requirements. All these variables lead to different solutions in DCD approaches as well as preservation and procurement techniques. The “hands off” time is 5 minutes for almost all centres around the world except for Zurich (10 minutes), some Australian centres (2 minutes) and Italy (notably, 20 minutes). Also, in some countries (such as the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Netherlands), ante mortem drug administration aiming at organ preservation is not allowed, while in other centres (for example in Belgium, Spain, Austria and France) it is legal to do so once the next of kin has been informed.

DCD donors in Italy

In Italy, heparin can only be given to the donor during the agonal phase, and cannulation is not allowed before the diagnosis of death, whilst femoral vessels wires can be positioned to simplify the upcoming cannulation. Essentially, in Italy it is legally allowed to retrieve organs from DCD donors; from a bioethical perspective, it should be emphasized that the current regulations seek to avoid disregarding the person’s will to donate their organs after death. On the other hand, the path to include DCD donors in clinical practice was complex and far from straightforward. In fact, it should be pointed out that transplant centres in Italy had to face the challenge of an extremely long warm ischemic “no-touch” period of 20 minutes, making organ preservation particularly demanding. In Italy, an uDCD program started in 2007, while the use of controlled donors was only introduced later in 2015 as a direct consequence of the previously mentioned different ethical issues between the two settings. The first uDCD program for kidney transplantation, the “Alba program”, was started in Pavia: according to this protocol, immediately after determination of death with circulatory criteria, ECMO support and then selective abdominal normothermic venous-arterial circulation is established (17). At first, this project had to face some major challenges, including involvement and cooperation with emergency services and the need for on-call dedicated DCD task force personnel. However, despite the long no-touch period required by the Italian legislation, the Alba program had the merit to show that uDCD is feasible even in our country. The second DCD program was started in Florence at the Careggi Teaching Hospital and managed to transplant both kidneys and liver (18). In 2015, the first successful DCD liver transplantation in Italy was performed at the Niguarda transplant centre in Milan. A DCD program has been active ever since. Normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) was used to assess and preserve abdominal organs, counteracting the prolonged warm ischemia time (19).

The Milan lung transplant centre’s experience

The Policlinico transplant centre in Milan has been a pioneer in lung transplantation with grafts from DCD donors. Our Lung-DCD program started in 2014 and was preceded by a long pre-clinical and an educational phase; at first, we focused on uDCD donors. Our protocol, which was designed for lung procurement only, was based on the observation that lung tissue can dissociate ischaemia from hypoxia, hence the possibility to preserve lungs for an extended period of time by using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Recruitment manoeuvres were performed following diagnosis of death and CPAP was employed. After obtaining consent by the next of kin, the donor was administered heparin and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was resumed for 3 minutes. Lungs were ventilated during procurement, and subsequently evaluated using EVLP (Figure 5) (20). In 2014 we performed the first lung transplantation from an uDCD donor in Italy: the recipient is still alive and in good condition. Our protocol differs from the one described by Steen and used by the Spanish group, as we do not insert chest tubes for topical cooling, leaving the body intact until the procurement in the operating theatre, at virtually no costs. This peculiar strategy allowed us to apply this protocol in both central hospitals with an extracorporeal life-support (ECLS) program, and less-equipped peripheral hospitals. Also, it guarantees an adequate time to face organisational issues during in-situ preservation and an adequate ex-vivo evaluation. After gaining some experience with the uncontrolled setting, we eventually decided to explore other options by including cDCDs in our project as well. In fact, at that time the concept of withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (WLSTs) when deemed futile, was beginning to spread and to be considered ethically suitable around ICUs in Italy, prompting us to adapt our project to these different settings. On the other hand, the growing experience on abdominal organs transplantation from DCD donors throughout Italian centres urged us to cooperate in order to establish a dedicated combined procurement protocol, which was drawn up by a multidisciplinary team (21). The required 20 minutes of no-touch posed a challenge for liver retrieval, as it inevitably suffers from a prolonged warm ischemia time: this obstacle was overcome by using NRP. In our protocol, we combined the use of NRP for abdominal organ preservation, in order to both minimize warm ischemia damage and assess the graft function, with our normothermic open-lung approach (Figure 6). The NRP stability is tested by closing the inferior vena cava through a tourniquet and clamping the aorta (Figure 7). All organs (lungs, kidneys, liver) are assessed through ex-situ perfusion, as they endure a prolonged functional warm ischemic time. Machine perfusion is considered particularly mandatory for DCD donors in an uncontrolled setting. This Full-DCD project began in October 2017: during the first 2 months, five cDCD donors from four different hospitals were managed according to this protocol. Two of these donors were ECDs, while another one was on ECLS support. In three out of five cases lungs were judged suitable and transplanted at our centre. To this day, all recipients are alive and in good health. In one case the lungs were deemed inadequate for transplantation due to infection, and therefore were not even retrieved; in another case, they showed bronchorrhea at the end of EVLP evaluation and could not be transplanted. Livers were used for transplantation in all five cases, with good outcomes; six out of ten procured kidneys were transplanted. These data showed that there were no detrimental effects on abdominal organs: performing a double NRP test allowed for a dynamic adjustment of flow settings. These excellent results pushed us to continue our path and reassured the abdominal surgeons. At our centre, from November 1st, 2014 to July 2019, 11 transplantation procedures were carried out with grafts coming from DCD donors; five of those were uDCDs and six were cDCDs. All patients are still alive. Remarkably, our combined retrieval DCD protocol helped increase the number of performed lung transplantation, showing promising results and no reduction in the number of transplanted abdominal organs. Furthermore, procurement from non-heart-beating donors allows us to avoid the cytokine storm and its damage to the organs. However, due to the prolonged ischemic time grafts from DCDs have to endure, we routinely use EVLP in order to assess the organs function. As some studies have already shown that ex-vivo evaluation is not mandatory for grafts retrieved from category III DCD donors (22), we are too considering reserving EVLP for uDCDs and for cDCDs when the in-vivo assessment demonstrate suboptimal graft function. In general, the transplantation experience with DCD donors has undeniably become relevant in our country. Over the last 5 years, the number of transplantation procedures performed in Italy with grafts from DCD donors has been increasing: in 2019, 115 out of 3,449 transplantations from deceased donors were from DCDs (4.5%). If we only consider lung transplantation, this rate rises to 8.5% and other centres have followed our experience in these years. In conclusion, our protocol offers a very adaptable approach that has been applied in various scenarios: cDCD and uDCD settings, isolated and combined thoracic and abdominal retrieval, hospitals with or without ECLS programs. At the expense of longer ischemic times, we prefer to optimise the lungs’ conditions by normothermic ventilation. By using this strategy, we avoid blindly perfusing the lungs before visual inspection and recruitment, which could result in inhomogeneous cold flushing in case of atelectasis or pleural effusion. It proved safe, as grafts function is assessed both in-situ during normothermic ventilation and ex-situ during normothermic perfusion, and it demonstrates the feasibility of a combined approach, overcoming the obstacle of prolonged warm ischemic time. The complexity of the program, however, requires a continuous education for the staff involved, especially for the uncontrolled setting. We are currently working on involving a growing number of hospitals in our project. Our experience shows the feasibility of a multi-organ donation from DCD donors, confirming it is possible to abide by the dead donor rule and to overcome the prolonged “no-touch” period required by law.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Jing Yu Chen and Michael Hsin) for the series “Highlights of the First International Symposium on Lung transplantation, Wuxi, China, 2019” published in Current Challenges in Thoracic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts-20-116/coif). The series “Highlights of the First International Symposium on Lung transplantation, Wuxi, China, 2019” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work (if applied, including full data access, integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis) in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by Ethics committee of Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Milano. Mortality risk factors in patients waiting and submitted to lung transplant. Ref. n° 181 (24/01/2017).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Chambers DC, Cherikh WS, Harhay MO, et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-sixth adult lung and heart-lung transplantation Report-2019; Focus theme: Donor and recipient size match. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:1042-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Legge 1 aprile 1999, n. 91 Disposizioni in materia di prelievi e di trapianti di organi e di tessuti. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=1999-04-15&atto.codiceRedazionale=099G0153&elenco30giorni=false#:~:text=note%3A%20Entrata%20in%20vigore%20della%20legge%3A%2016%2F4%2F1999&text=1.&text=La%20presente%20legge%20disciplina%20il,e%20di%20trapianto%20di%20organi

- Legge 29 dicembre 1993, n. 578. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1994/01/08/094G0004/sg

- D.M. 11 aprile 2008, aggiornamento del D.M. 22 agosto 1994, n. 582. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2008/06/12/08A04067/sg

- Available online: http://www.trapianti.salute.gov.it/trapianti/archivioDatiCnt.jsp

- Schiavon M, Faggi G, Rosso L, et al. Outcomes and risk factors identification in urgent lung transplantation: a multicentric study. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:4746-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palleschi A, Benazzi E, Rossi CF, et al. Lung Allocation Score System: First Italian Experience. Transplant Proc 2019;51:190-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boffini M, Ricci D, Bonato R, et al. Incidence and severity of primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation using rejected grafts reconditioned with ex vivo lung perfusion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;46:789-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiavon M, Faggi G, Rebusso A, et al. Extended criteria donor lung reconditioning with the organ care system lung: a single institution experience. Transpl Int 2019;32:131-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valenza F, Rosso L, Coppola S, et al. Ex vivo lung perfusion to improve donor lung function and increase the number of organs available for transplantation. Transpl Int 2014;27:553-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fumagalli J, Rosso L, Gori F, et al. Early pulmonary function and mid-term outcome in lung transplantation after ex-vivo lung perfusion - a single-center, retrospective, observational, cohort study. Transpl Int 2020;33:773-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palleschi A, Rosso L, Schiavon M, et al. Is "lung repair centre" a possible answer to organ shortage?-transplantation of left and right lung at two different centres after ex vivo lung perfusion evaluation and repair: case report. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:E318-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Alessandro AM, Hoffmann RM, Knechtle SJ, et al. Controlled non-heart-beating donors: a potential source of extrarenal organs. Transplant Proc 1995;27:707-9. [PubMed]

- Steen S, Sjöberg T, Pierre L, et al. Transplantation of lungs from a non-heart-beating donor. Lancet. 2001;357:825-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Raemdonck DE, Jannis NC, Rega FR, et al. Extended preservation of ischemic pulmonary graft by postmortem alveolar expansion. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:801-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kootstra G, Daemen JH, Oomen AP. Categories of non-heart-beating donors. Transplant Proc 1995;27:2893-4. [PubMed]

- Geraci PM, Sepe V. Non-heart-beating organ donation in Italy. Minerva Anestesiol 2011;77:613-23. [PubMed]

- Peris A, Lazzeri C, Cianchi G, et al. Implementing a donation after circulatory death program in a setting of donation after brain death activity. Minerva Anestesiol 2018;84:1387-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Carlis L, Lauterio A, De Carlis R, et al. Donation after cardiac death liver transplantation after more than 20 minutes of circulatory arrest and normothermic regional perfusion. Transplantation 2016;100:e21-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valenza F, Citerio G, Palleschi A, et al. Successful transplantation of lungs from an uncontrolled donor after circulatory death preserved in situ by alveolar recruitment maneuvers and assessed by ex vivo lung perfusion. Am J Transplant 2016;16:1312-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palleschi A, Tosi D, Rosso L, et al. Successful preservation and transplant of warm ischaemic lungs from controlled donors after circulatory death by prolonged in situ ventilation during normothermic regional perfusion of abdominal organs. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2019;29:699-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levvey BJ, Harkess M, Hopkins P. Am J Transplant 2012;12:2406-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Palleschi A, Musso V, Mendogni P, Zanierato M, De Feo TM, Cardillo M, Nosotti M. Donation after circulatory death program in Italy. Curr Chall Thorac Surg 2022;4:5.