Tracheal surgery in Germany

Introduction

First published literature concerning tracheal surgery in Germany was presented in 1881 by Themistokles Gluck. He demonstrated the feasibility of tracheal resection and end-to-end anastomosis in dogs for the first time (1). Few years later, in 1915, Gluck and his colleague Johannes Soerensen published a first description of tracheal resection and airway reconstruction in humans (2), describing the cases of two individuals with malignant stenosis of the trachea. In both patients, tracheal sleeve resection was performed, a R0 margin was achieved and a 24-month follow-up showed no recurrence.

The challenging problem in tracheal surgery with end-to-end-anastomosis is reduction of tension at the anastomosis to allow a sufficient healing. During the 20th century, several surgeons developed approaches to improve tracheal mobilisation enabling extended resection without intense tension at the anastomosis.

During the same period, multiple techniques of covering the anastomosis with tissue flaps were developed (3) and especially the work of Hermes C. Grillo was a landmark in progress of tracheal surgery. Grillo and colleagues presented a new technique, allowing to resect half of the trachea and still facilitating a sufficient end-to-end anastomosis (4).

The increasing use of extracorporal membrane oxygenation is one of the latest innovations providing full respiratory support in tracheal surgery (5).

Another recent development is the progress of minimal invasive surgery. These techniques also affect the field of tracheal surgery including tracheal resection and reconstruction by mediastinoscopic approach (6) as well as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) (7). The first circumferential resection and primary end-to-end anastomosis of the trachea, operated via VATS, was already published by Nakanishi in 2005 (8) and several surgeons adopted and enhanced this approach, up to the latest reports of carinal sleeve resection carried out by uniportal VATS.

The work of Jianxing He and colleagues needs to be highlighted in this field. They published multiple case reports and case series evidently revealing the progress of advanced thoracic surgery. These contributions illustrate the evolution from resection of a tracheal mass with three-port-VATS under non-intubated anaesthesia (9), followed by VATS with carinal reconstruction (10), to uniportal VATS for tracheal resection in a spontaneous breathing patient (11). Certainly, it must be mentioned that uniportal non-intubated VATS is not the standard approach for tracheal surgery in German departments for thoracic surgery.

Methods and key contents

We performed a literature research in PubMed concerning tracheal surgery and evaluated data from “Federal Statistical Office Germany”. In the later we requested extraction of data from German diagnosis-related-groups (G-DRG)-system database concerning procedures and diagnoses affecting tracheal resection and management of tracheal injury.

The exact amount of each procedure is diagrammed in case of more than 3 procedures per year, otherwise the number is presented as “below 3” (<3). The Number of deceased patients related to a diagnosis or the treatment is not directly related to the intervention, but records death during the same hospitalisation period as encoded in G-DRG.

Tracheal resection

Certainly, primary neoplasms of the trachea are rare, most common entities being squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. More often neoplasms of the trachea are secondary and the initial tumours origin from the esophagus, thyroid gland or the lung (12).

Therefore the most important indication for tracheal resection is tracheal stenosis, due to iatrogenic reasons like tracheostomy or cuff-induced after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Other forms of tracheal stenosis are idiopathic or secondary caused by compression, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, granulomatosis with polyangitis or tracheopathia osteochondroplastica (13).

Signs and symptoms may vary in every patient, because the individual might be adopted to respiratory insufficiency after a slow process of the disease. On the other hand some patients show notable signs like dyspnea or stridor and the situation might be life-threatening. First obvious signs often appear only after tracheal restriction of more than 50%.

In every tracheal disease or injury the bronchoscopic evaluation is the most important diagnostic tool leading to exact diagnosis and management decision. Other methods, like body plethysmography or radiologic procedures can help to identify the severity of the disease, but only bronchoscopy is able to show the extent of a tracheal mass, injury or stenosis (13).

For the treatment of a tracheal mass several methods are available. The tumor might be resected via rigid fiber optic bronchoscopy, a restriction might be dilatated with a bougie, stent implantation can be performed and in some cases there is the indication for surgical approach (14).

The keystone of every resection of the trachea is to avoid tension on the end-to-end anastomosis. This is independent of the surgical approach being cervical, transsternal or via thoracotomy. It is independent from surgeon’s experience and from patient’s characteristics. Tension on the anastomosis can lead to insufficiency, bleeding, infections and re-stenosis, so it needs to be avoided (15).

In the most cases of tracheal stenosis the tracheal segment which needs to be resected comprises 2–4 cm and is located in the cervical part due to tracheostomy or prolonged mechanical ventilation. The surgical approach is cervical in these cases and mobilisation of the trachea is necessary just for 1 cm to both sides of the resected part. Further mobilisation can lead to injury of surrounded organs or impairment of tracheal perfusion (13).

Especially during percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy an injury of the cricoid cartilage may occur. In these cases a challenging subglottic cricotracheal reconstruction may be indicated. Nevertheless, even in specialized centers for thoracic surgery tracheal resection remains to be one of the most challenging procedures (16).

Tracheal injury

Tracheal injury is basically classified in two forms, based on the mechanism of laceration. First is the iatrogenic tracheal laceration as a rare, but life-threatening complication of endobronchial intubation. The other one is a traumatic tracheal lesion following blunt chest trauma or penetration.

The incidence of tracheal injury after endotracheal intubation, dependant on the manner of intubation is approximately 0.005% in a single-lumen intubation, 0.05–0.19% in a double-lumen intubation and 0.2–0.7% after percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (17).

Subcutaneous or mediastinal emphysema, dyspnea and hemoptysis are typical signs and symptoms of tracheal injury and may occur delayed. Nevertheless, clinically apparent injuries are often life threatening and patients are in need of rapid and experienced evaluation and treatment, as iatrogenic tracheal laceration is a complication accompanied with a high mortality, stated with up to 42% (18). Reasons for the high mortality are alleged to be the underlying diseases, which led to intubation. Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome is one the most important causes of death in perioperative management for iatrogenic tracheal laceration.

Unfortunately, criteria of decision-making for treatment are inconsistent and vary from conservative management to surgery dependant on clinical status, necessity of further mechanical ventilation and depth of the lesion (17).

In stable patients without need of mechanical ventilation, conservative management is an appropriate treatment and stenting of the trachea is a common procedure. In patients with transmural injury or necessity of mechanical ventilation surgical management of iatrogenic tracheal lesions is still the gold standard of treatment (19). One important disadvantage of conservative management is the development of a tracheal instability without surgical intervention (20).

In 1995 Angelillo-Mackinlay published first results of a transcervical approach for surgical treatment of tracheal laceration (21). This approach enables the management of lesions down to the carina. Lacerations of the main bronchus are reached via thoracotomy (22). Aim of transcervical approach is the reduction of mortality by avoiding necessity of thoracotomy and causing less trauma in these patients.

The mechanism of tracheal injury after blunt thoracic trauma is either thoracic compression in combination with glottis closure or sudden high-speed deceleration trauma. In contrast to iatrogenic tracheal tear, with longitudinal injury of the pars membranaceous, in these cases injury mostly occurs as disrupture of the trachea or mainstem bronchus.

Tracheobronchial avulsion resulting from blunt trauma is a rare but serious condition. Blunt chest trauma represent just 3% of all tracheobronchial injuries, but prehospital mortality is up to 80%. In most cases the intrathoracic tracheobronchial tree is involved. In contrast, cervical trachea is commonly affected in case of stab or gunshot wounds (23).

Signs and symptoms vary from asymptomatic patients up to rapid drop in O2 saturation and acute respiratory insuffiency as a life-threatening situation. Common signs and symptoms are dyspnea, subcutaneous or mediastinal emphysema and pneumothorax (23).

In most cases surgical management is mandatory. Surgical approach depends on site of the injury and transcervical approach, thoracotomy or sternotomy are standard approaches. In disrupture of the tracheobronchial tree after blunt chest trauma a tracheal or bronchial resection with end-to-end anastomosis is advisable. Tracheal injury due to penetration usually requires surgical management in form of debridement and primary suture.

Potential consequence of an undiagnosed tracheal injury in initial asymptomatic patient is the development of tracheal stenosis, possibly demanding further intervention (13).

Findings and discussion

The Federal Statistical Office Germany extracted data of the G-DRG system related to the following main diagnoses:

- Neoplasm of the trachea; n=367 in 2018;

- Injury of the neck, not further described; n=24 in 2018;

- Injury of the trachea, pars thoracica; n=66 in 2018;

- Acquired tracheal stenosis; n=1,070 in 2018;

- Disease of upper airway, not further described; n=287 in 2018;

- Tracheal stenosis after medical intervention; n=740 in 2018;

- Congenital malformation of the trachea; n=83 in 2018.

The number of diagnosis and the development between 2014 and 2018 is shown in Figure 1.

The most common tracheal operation in Germany is the surgical closure of a tracheostoma, which was performed almost 5000 times per year between 2014 and 2018. The mortality of these patients at the same hospitalisation period was 1% (Table 1). Other procedures in tracheal surgery in Germany and the number of deceased patients is given in Table 1. It is shown that most interventions at the trachea are bronchoscopic, like dilatation with or without implantation of a stent or excision of malignant tissue. In surgical management, open surgery is the usual approach compared to VATS, as mentioned introductory.

Table 1

| Procedure | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excision of tracheal tissue, open surgery | 252 | 258 | 276 | 282 | 207 |

| Deceased patients | 9 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 9 |

| Excision of tracheal tissue, thoracoscopic | 6 | 16 | 12 | 11 | 5 |

| Deceased patients | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Excision of tracheal tissue, bronchoscopic | 632 | 636 | 609 | 533 | 541 |

| Deceased patients | 24 | 16 | 13 | 14 | 22 |

| Tracheal resection with end-to-end anastomosis | 124 | 162 | 148 | 154 | 146 |

| Deceased patients | 7 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Tracheal resection with tracheostomy | 124 | 172 | 167 | 161 | 174 |

| Deceased patients | 12 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 19 |

| Reconstruction after tracheal injury | 178 | 189 | 149 | 179 | 189 |

| Deceased patients | 33 | 40 | 28 | 26 | 35 |

| Destruction of malignant tissue in trachea, open surgery | 46 | 46 | 40 | 40 | 36 |

| Deceased patients | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Destruction of malignant tissue in trachea, bronchoscopic | 464 | 508 | 435 | 436 | 548 |

| Deceased patients | 25 | 25 | 21 | 23 | 31 |

| Closure of a tracheostomy | 4,964 | 4,879 | 4,997 | 4,976 | 4,823 |

| Deceased patients | 54 | 46 | 37 | 44 | 48 |

| Resection of tracheal stenosis with end-to-end anastomosis | 46 | 70 | 66 | 67 | 75 |

| Deceased patients | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Resection of tracheal stenosis, other | 190 | 180 | 199 | 233 | 166 |

| Deceased patients | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Treatment of tracheal stenosis with stent | 100 | 108 | 127 | 149 | 130 |

| Deceased patients | 11 | 10 | 13 | 9 | 11 |

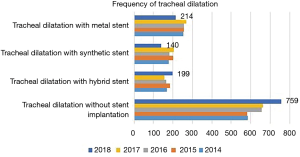

| Tracheal dilatation without stent implantation | 759 | 664 | 656 | 582 | 585 |

| Deceased patients | 35 | 25 | 24 | 28 | 30 |

| Tracheal dilatation with hybrid stent | 199 | 156 | 165 | 184 | 170 |

| Deceased patients | 37 | 27 | 32 | 29 | 35 |

| Tracheal dilatation with synthetic stent | 140 | 205 | 182 | 201 | 180 |

| Deceased patients | 14 | 21 | 12 | 16 | 19 |

| Tracheal dilatation with metal stent | 214 | 271 | 257 | 257 | 254 |

| Deceased patients | 39 | 53 | 30 | 41 | 31 |

| Carinal resection | 19 | 13 | 19 | 18 | 11 |

| Deceased patients | 5 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

Tracheal dilatation with or without implantation of a stent is performed for tracheal stenosis or tracheal neoplasm and is one of the most common procedures in treatment of tracheal diseases in Germany (Table 1, Figure 2).

Tracheal injury

In 2018, 66 patients with tracheal injury were treated in Germany (Figure 1). In 40 of these patients bronchoscopic evaluation was performed. In 10 more cases bronchoscopy was supplemented by bronchoalveolar lavage. Rigid bronchoscopy for evaluation of tracheal injury was performed less than three times.

Fourteen patients underwent computed tomography (CT) with contrast of the neck and four patients CT without contrast of the neck. Chest-CT with contrast was conducted in 27 cases. Thirteen patients received chest-CT without contrast.

Primary suture of the laceration was performed in 32 cases. Eight patients received a temporary tracheostomy and in six individuals the tracheostomy was permanent. In 2018, 11 of the 66 patients with tracheal injury underwent a cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The analysis of data of procedures performed in Germany in 2018 shows 6 cases with tracheal resection with end-to-end anastomosis after blunt injury and 189 procedures with reconstruction after tracheal injury. Unfortunately these data do not differentiate mechanism of injury and probably procedures due to accidental intraoperative injury are included.

Tracheal neoplasm

Three hundred and sixty-seven patients with tracheal neoplasm were treated in Germany in 2018 (Figure 1).

One hundred and sixty-eight patients underwent flexible bronchoscopy and in 65 cases bronchoscopy was performed in rigid technique. Chest-CT with contrast was conducted in 106 individuals and CT with three-dimensional analysis was performed in 50 patients.

In 72 cases the histopathologic evaluation of tracheal neoplasm for performed by bronchoscopic incision of the trachea and in 29 patients by bronchoscopic incision of a bronchus.

Management of tracheal neoplasm was predominantly multimodal. Surgical resection, bronchoscopic destruction of malignant tissue, radiotherapy and chemotherapy were performed in more than 20 cases each (Table 2).

Table 2

| Procedure | 2018 (n=367) | 2017 (n=319) | 2016 (n=375) | 2015 (n=311) | 2014 (n=366) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible bronchoscopy | 168 | 125 | 165 | 152 | 168 |

| Rigid bronchoscopy | 65 | 57 | 70 | 75 | 76 |

| Endoscopic incision, trachea | 72 | 68 | 82 | 56 | 65 |

| Endoscopic incision, bronchus | 29 | 20 | 30 | 27 | 26 |

| Body plethysmography | 102 | 94 | 111 | 83 | 97 |

| CT of the neck without contrast | 9 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 7 |

| Chest CT without contrast | 19 | 22 | 25 | 24 | 15 |

| CT of the neck with contrast | 46 | 40 | 35 | 31 | 33 |

| Chest CT with contrast | 106 | 98 | 118 | 81 | 99 |

| Head CT without contrast | 14 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| Head CT with contrast | 14 | 22 | 20 | 21 | 31 |

| Head MRI without contrast | 9 | 5 | 15 | 4 | 6 |

| Head MRI with contrast | 26 | 17 | 28 | 21 | 23 |

| 3-dimensional CT analysis | 50 | 42 | 35 | 33 | 21 |

| Resection of tracheal tissue, open | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Resection of tracheal tissue, bronchoscopy | 20 | 28 | 19 | 15 | 25 |

| Resection with end-to-end anastomosis | 13 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 12 |

| Resection with tracheotomy | <3 | <3 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Resection, other | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Endoscopic dilatation without stent implantation | 12 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 18 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, hybrid | 4 | <3 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, synthetic | <3 | <3 | 6 | 3 | <3 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, metal | 9 | 8 | 12 | 8 | 9 |

| Destruction of tissue, bronchoscopic | 21 | 24 | 31 | 15 | 19 |

| Destruction of tissue, cryo-biopsy | 9 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 12 |

<3, less than three times; CT, computed tomography.

Tracheal stenosis

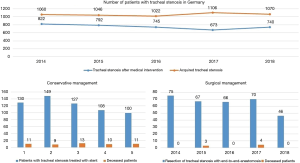

The underlying ICD-10-GM to the G-DRG differentiates two codes for tracheal stenosis. First one is the “acquired tracheal stenosis” (ATS), the other one is the “tracheal stenosis following medical intervention” (TSMI). The number of cases is shown in Figures 1,3.

Clinical diagnostics are based on bronchoscopic evaluation. Flexible bronchoscopy was performed 582 times in 2018 for ATS and 359 times for TSMI. Additional bronchoscopic evaluation in rigid technique took place 288 cases in 2018 for ATS and in 218 cases for TSMI. In 2018, chest-CT with contrast was performed 154 times and 77 times without contrast for ATS. Patients with TSMI received chest-CT with contrast 66 times and in 47 times without contrast.

The preferred management was conservative, as shown in Figure 3. Most common method was the dilatation of the stenosis without implantation of a stent (203 cases in 2018 for ATS and 111 cases in 2018 for TSMI), followed by bronchoscopic excision of tissue in 71 patients in 2018 for ATS and in 48 patients in 2018 for TSMI. Surgical management consisted of resection of tracheal stenosis with end-to-end anastomosis in 20 cases in 2018 for ATS and 52 cases for TSMI. Additional information of encoded procedures related to patients with tracheal stenosis between 2014 and 2018 is shown in Table 3 for ATS and Table 4 for TSMI.

Table 3

| Procedure | 2018 (n=1,070) | 2017 (n=1,106) | 2016 (n=1,022) | 2015 (n=1,046) | 2014 (n=1,060) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic laryngoscopy | 266 | 236 | 218 | 245 | 224 |

| Flexible bronchoscopy | 582 | 614 | 516 | 512 | 540 |

| Flexible bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage | 89 | 76 | 83 | 91 | 68 |

| Flexible bronchoscopy, other | 93 | 106 | 107 | 104 | 128 |

| Rigid bronchoscopy | 288 | 346 | n.a. | 342 | 310 |

| Rigid bronchoscopy, other | 18 | 16 | n.a. | 19 | 13 |

| Body plethysmography | 85 | 81 | 89 | 89 | 83 |

| CT of the neck without contrast | 60 | 66 | 46 | 57 | 67 |

| Chest CT without contrast | 77 | 98 | 69 | 80 | 98 |

| CT of the neck with contrast | 106 | 121 | 98 | 113 | 107 |

| Chest CT with contrast | 154 | 158 | 141 | 159 | 139 |

| 3-dimensional CT analysis | 117 | 129 | 91 | 99 | 89 |

| Excision of tissue, open surgery | 13 | 7 | 8 | 22 | 10 |

| Excision of tissue, bronchoscopic | 71 | 65 | 68 | 58 | 44 |

| Resection with end-to-end anastomosis | 20 | 43 | 30 | 33 | 35 |

| Resection with tracheotomy | 8 | 6 | 4 | <3 | <3 |

| Resection, other | 4 | 6 | 5 | <3 | 6 |

| Destruction of tissue, bronchoscopic | 51 | 59 | 45 | 49 | 97 |

| Destruction of tissue, other | 11 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 4 |

| Endoscopic dilatation without stent implantation | 203 | 167 | 159 | 165 | 138 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, hybrid | 32 | 19 | 13 | 25 | 14 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, synthetic | 27 | 45 | 37 | 43 | 33 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, metal | 17 | 37 | 32 | 36 | 35 |

| Resuscitation | 14 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 13 |

n.a., not available; <3, less than three times; CT, computed tomography.

Table 4

| Procedure | 2018 (n=740) | 2017 (n=673) | 2016 (n=749) | 2015 (n=792) | 2014 (n=822) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic laryngoscopy | 134 | 121 | 154 | 115 | 158 |

| Diagnostic pharyngoscopy | 56 | 44 | 65 | 44 | 47 |

| Flexible bronchoscopy | 359 | 335 | 360 | 401 | 346 |

| Flexible bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage | 42 | 32 | 45 | 44 | 40 |

| Flexible bronchoscopy, other | 67 | 51 | 56 | 66 | 72 |

| Rigid bronchoscopy | 218 | 199 | 249 | 237 | 262 |

| Rigid bronchoscopy, other | 37 | 32 | 59 | 58 | 72 |

| Body plethysmography | 166 | 166 | 173 | 181 | 185 |

| CT of the neck without contrast | 40 | 33 | 32 | 38 | 36 |

| Chest CT without contrast | 47 | 42 | 41 | 43 | 52 |

| CT of the neck with contrast | 52 | 47 | 51 | 48 | 56 |

| Chest CT with contrast | 66 | 56 | 49 | 68 | 66 |

| 3-dimensional CT analysis | 57 | 49 | 43 | 48 | 56 |

| Excision of tissue, open surgery | 10 | 9 | 14 | 11 | 15 |

| Excision of tissue, bronchoscopic | 48 | 41 | 43 | 45 | 44 |

| Resection with end-to-end anastomosis | 52 | 47 | 46 | 52 | 44 |

| Resection with tracheotomy | 5 | 3 | <3 | 3 | 5 |

| Resection, other | 3 | <3 | 9 | 13 | 5 |

| Destruction of tissue, Bronchoscopic | 43 | 62 | 53 | 51 | 54 |

| Management of tracheal stenosis with end-to-end anastomosis | 13 | 24 | 17 | 19 | 23 |

| Management of tracheal stenosis with stent | 20 | 21 | 25 | 26 | 33 |

| Management of tracheal stenosis, other | 35 | 25 | 45 | 45 | 36 |

| Endoscopic dilatation without stent implantation | 111 | 90 | 99 | 79 | 82 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, hybrid | 3 | 4 | 10 | <3 | 8 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, synthetic | 25 | 24 | 20 | 34 | 28 |

| Endoscopic dilatation with stent implantation, metal | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

<3, less than three times; CT, computed tomography.

Conclusions

Management of tracheal diseases is predominately performed by bronchoscopic procedures. This affects diagnostic procedures as well as therapeutic interventions. It is conspicuous that there is a lack between the number of encoded diagnoses in every field of tracheal diseases and the number of encoded diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Explanations might be incorrect encoding by physicians or redundant treatment in asymptomatic or palliative patients. The data of the Federal Statistical Office Germany doesn’t provide sufficient answer to this question.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Francesco Zaraca, Reinhold Perkmann, Luca Bertolaccini and Roberto Crisci) for the series “Thoracic Surgery Without Borders” published in Current Challenges in Thoracic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts.2019.12.02/coif). The series “Thoracic Surgery Without Borders” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gluck T, Zeller A. Die prophylaktische Resektion der Trachea. Arch Klin Chir 1881;26:427-36.

- Soerensen J. Zwei Fälle von Totalexstirpation der Trachea wegen Karzinom. Archiv Laryngol Rhinol 1915;29:188-204.

- Grillo HC. Development of tracheal surgery: a historical review. Part 1: Techniques of tracheal surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:610-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grillo HC, Dignan EF, Miura T. Extensive resection and reconstruction of mediastinal trachea without prosthesis or graft: an anatomical study in man. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1964;48:741-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rinieri P, Peillon C, Bessou JP, et al. National review of use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as respiratory support in thoracic surgery excluding lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015;47:87-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herrmann D, Schoch M, Hecker E. Videomediastinoskopische Tracheateilresektion und Rekonstruktion. Zentralbl Chir 2017;142:S67-S112.

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, Yang Y, Stupnik T, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic bronchovascular, tracheal and carinal sleeve resections†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:i6-16. [PubMed]

- Nakanishi K, Kuruma T. Video-assisted thoracic tracheoplasty for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the mediastinal trachea. Surgery 2005;137:250-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li S, Liu J, He J, et al. Video-assisted transthoracic surgery resection of a tracheal mass and reconstruction of trachea under non-intubated anesthesia with spontaneous breathing. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:575-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- He J, Wang W, Li J, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery tracheal resection and carinal reconstruction for tracheal adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:198-203. [PubMed]

- Guo M, Peng G, Wei B, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in tracheal tumour under spontaneous ventilation anaesthesia Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;52:392-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Behringer D, Könemann S, Hecker E. Treatment Approaches to Primary Tracheal Cancer. Thorac Surg Clin 2014;24:73-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volmerig J, Hecker E. Chirurgie der Trachea – Tracheal Surgery. Zentralbl Chir 2017;142:320-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bolliger CT, Sutedja TG, Strausz J, et al. Therapeutic bronchoscopy with immediate effect: laser, electrocauerty, argon plasma coagulation and stents. Eur Respir J 2006;27:1258-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright CD, Grillo HC, Wain JC, et al. Anastomotic complications after tracheal resection: prognostic factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;128:731-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Porhanov VA, Poliakov IS, Selvaschuk AP, et al. Indications and results of sleeve carinal resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;22:685-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herrmann D, Volmerig J, Al-Turki A, et al. Does less surgical trauma result in better outcome in management of iatrogenic tracheobronchial laceration? J Thorac Dis 2019;11:4772-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hofmann HS, Rettig G, Radke J, et al. Iatrogenic ruptures of the tracheobronchial tree. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;21:649-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cassada DC, Munyikwa MP, Moniz MP, et al. Acute injuries of the trachea and major bronchi:importance of early diagnosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:1563-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Welter S. Repair of tracheobronchial injuries. Thorac Surg Clin 2014;24:41-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Angelillo-Mackinlay T. Transcervical Repair of Distal Membranous Tracheal Laceration. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;59:531-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grewal HS, Dangayach NS, Ahmad U, et al. Treatment of tracheobronchial injuries: a contemporary review. Chest 2019;155:595-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Symbas PN, Justicz AG, Ricketts RR. Rupture of the airways from blunt trauma: treatment of complex injuries. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;54:177-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Herrmann D, Volmerig J, Oggiano M, Ewig S, Hecker E. Tracheal surgery in Germany. Curr Chall Thorac Surg 2020;2:7.